Edwin Perry in later years. (Rob Grandchamp Collection)

These letters were written by 18 year-old Edwin Perry (1844-Aft1880), the son of Daniel Bliss Perry (1802-1879) and Lydia Ann Carpenter (1805-1883) of Rehoboth, Bristol County, Massachusetts. Edwin learned the trade of manufacturing bobbins (occupation called “turner”) for cotton factories from his father.

For some reason, Edwin did not join the other boys from Rehoboth in Company H of the 40th Massachusetts. Rather, he enlisted in Company C, 11th Rhode Island Infantry. He mustered out of the service on 13 July 1863. He was married to Ella J. Perry (1851-19xx) sometime after the war and continued to reside and carry on the family business in the vicinity of Rehoboth, Massachusetts.

TRANSCRIPTION OF LETTERS

In Camp near Miner’s Hill, Virginia

October 21, 1862

Dear Brother,

Your favors of the 10th and 17th instant I received last evening and I acknowledge the receipt of ten dollars — many thanks for it.

Last night we received marching orders and early this morning after partaking of an early breakfast, this regiment together with the 133rd New York and 22nd Connecticut Regiments took up our line of march for this place. The weather was quite cool so that we were greatly favored in carrying our load which consisted of a well-stuffed knapsack, haversack, canteen, musket, and equipments with forty rounds of cartridges.

We reached this ground about ten o’clock this morning and after marching and countermarching for another hour at last halted on a turnip field and a orchard. By two o’clock we had our tent put up and now four o’clock all the boys excepting [Pvt. Orin F.] Munroe are asleep. He is writing like me.

We received orders not to be too particular about putting up tents as we were to march again tomorrow — some say further to the right — others toward Harpers Ferry — and others to our old camping ground and from thence to Washington and then to Port Royal. The latter seems to have the best foundation as two companies which were to go on picket duty after receiving their rations, packing their clothes, marching some distance were ordered back, and if we were going but a few miles in any direction, they would not [have] been recalled.

In reply to your questions I would state that we’re last I knew or heard (the orders are read at dress parade) in Gen. [Heber] Cowden’s Brigade, Gen. Abercrombie’s Division, and Gen. Heintzleman’s Army Corps of the defense of Washington. I think the captain is improving in his way of discipline.

We are now about eight miles from Washington. My health is and has been as good as I could ask for. As far as sleeping on the ground is concerned, I do not dislike it in warm weather but when it is cold, I’d rather sleep in a tent.

I am sorry that Father’s health is so poor but he must not worry himself on my account as I am enjoying myself “tip top.”

About obtaining Government small currency I would state that it is about the only kind of change in circulation here but then I think it would be very difficult to obtain any amount. But if I can do so, I will send it on to you.

Send my love to all the folks. Tell Ida I send her a kiss. We move so often that do do not have chance to think about any person as anything. The 40th Massachusetts containing the Attleboro & Rehoboth Companies of three year’s men is in our brigade and is encamped near us.

No more at present. Yours in haste.

— Edwin Perry, Co. C, 11th Regiment R.I.V., Washington D. C.

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Hospital

January 1, 1863

Dear Brother,

Your welcome letter of the 27th came duly to hand and with it comes the new year fraught with a greater interest than you or I ever saw for in that time we are to see the restoration or downfall of the American Union.

Eight weeks ago today I was brought to this place and the prospect is that I shall soon be able to leave without help. I think within the last ten days I have gained fifty per cent. I feel as well as ever I did although I have yet my strength to gain.

Stuart’s Rebel cavalry are making themselves to home around here. Five thousand being exported near Lewinsville some three or four miles from here. The brigade has been kept under arms for the last two days with orders to march at a moment’s notice. Last night about two o’clock I heard cannonading off to the right of the line and a few moments the long rolls was beat commencing in the Mass. and then to the Conn., R. I., New York, and Virginia, but after being out about a half an hour they returned to their quarters.

This afternoon I have walked three quarters of a mile and do not feel much fatigue. I see you have got to be quite a lawyer by comparing one letter with another of mine but the first statement you made is partly incorrect. I said in substance tell father not to hold out such inducements as he wrote to me about as Mr. Baker could not take his son home and so he could not for a discharge is not obtained in a day nor a week, but often takes two or three months. I think his was obtained in about six weeks. His discharge reached here last Saturday. It could not have been obtained a day sooner. Five weeks ago or about that I wrote the letter in which I made my first statement. When I wrote my second the Doctor was expecting his papers every day and friends had written to that effect no less than three times. Now for the reason why one discharge papers take twice as long as another. When the Regimental Surgeon thinks a man incapable of duty for the length of time he has enlisted he makes out papers stating the symptoms of the disease with which he is afflicted. This he takes to the Division Surgeon who, if he is satisfied, sends it forward. If not and he wishes to examine the case himself, he returns the papers and perhaps a month or six weeks afterwards he visits this hospital and examines the patient.

Now for the second question at issue. The rations at this hospital are as follows: Every morning, two slices of bakers bread averaging about three quarters of an inch in thickness of the size of a common six cent loaf, and butter enough for one slice. Dinner first day: roast beef & slice of bread; Dinner 2nd day: corned beef & slice of bread; Dinner 3rd day: steak and slice of bread; Dinner 4th day: soup & slice of bread; Dinner 5th day: baked beans & slice of bread. Supper: two slices bread, six days in a week; rice one day; together with a cup of tea. These are full rations which are all a person like myself can get. Once or twice we have had chicken soup served out as rations. I hope that now when you put that and that together that everything will join harmoniously. In my next letter I propose to give you the rations in camp and on the march so you must keep this and the next as letters of reference.

Yesterday the pay roll was made out for the last two months, but no money comes yet from best of all reasons, as the paymaster General told our Major “that there was no money in the treasury to pay the soldiers with.” “That’s what’s the matter” out in Virginia, but I close my letter by wishing you a Happy New Year, — Edwin Perry.

Hospital [Regiment encamped at Miner’s Hill, Va.]

January 8, 1863

Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 3rd instant has been received together with a letter from father which I received last night. I continue to gain strength with every effort. I have walked up to camp and back again every day for a week — some days twice as far.

The box you sent is a rich treat, I tell you. I am living high and sleeping in the hospital. Yesterday the Doctor gave me my discharge from this institution and told me to report at camp but the head nurse has took the responsibility of keeping me here a while longer. He thought I was not strong enough to endure camp life. I’d rather stay here a week longer than to go to camp [just] now. There has been another sudden change in the weather from warm to cold accompanied by high winds which are very uncomfortable on these high hills where the division is encamped.

Yesterday they brought a man here who has had the fever and ague together with convulsions. During these times, it takes four men to hold him. This forenoon he has had one chill and four convulsions. He can not stand them a great while longer and live. When he is reasonable, he cries considerable and says he never shall get home. This a solemn sight but this is one of the fortunes of war. But a person gets used of these things seeing it continually before him. I saw a case of sympathetic mania today in the case of one of the patients. Soon after the man had passed through the convulsions, I spoke of this patient (who has the pleura pneumonia) was taken in the same way as other although not quite as hard. As I now write, one of these men is on the way to the General Hospital at Washington; the other will probably go tomorrow. They can’t go too soon for me.

The regiment has again resumed its wonted routine of duty — the great scare of [Jeb] Stuart’s Cavalry being over. ¹ One day this week, one of the 16th Virginia soldiers undertook to run the picket near Falls Church, but his running was short for the shure sped bullet finished his existence. The picket [who shot him] was taken to the General who told him that he had done perfectly right and to do the same in a similar case. General Abercrombie, commander of the division, told the men in a speech that they got to do picket and guard duty until they went home if it killed every man in the division.

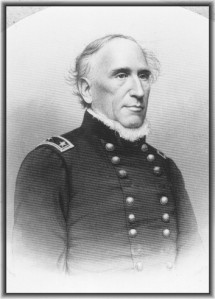

Robert Cowdin commanded a Brigade in Gen. Abercrombie’s Division (1863)

Gen. [Robert] Cowdin, our Brigadier, is all fight — always. When carrying on a social conversation, he has to tell of the THIRTEEN BATTLES and SIX SKIRMISHES in which he has been actor. He told the boys the other night he hoped everyone would get hit. He said that he had been hit six times. ²

Mr. Munroe’s son continues to be off duty. The climate does not agree with him.

The regiment does very little but guard and picket duty. ³ Five companies do the picket duty for one month, going out every four days. The other three regiments composing the brigade taking their turn. Four companies do the guard duty at camp. One company on detached service, guarding the 1st Maryland Cavalry from skedaddling. The 16th Virginia is very much like them. The general does not trust them on any kind of duty outside the picket line. If they went on picket, they would all run away.

I said in my last letter that I would write you something about the rations of camp and out on the march. Our rations at this distance from Washington are very near as follows — of soft bread in one week we receive or at least are allowed five days rations. each days rations consisting of one loaf of bakers bread the six of our six cent loafs, and two days rations of hard crackers. Of meat we are allowed fat pork fried nearly every morning, boiled ___ two days in a week. Beef steak once. Beef soup. twice, beans twice. Rice three times a week, cooked for supper together with coffee or tea twice a day.

One the march as far as I have had any experience and from what I can learn from others, they do not get much more than hard tack & salt horse.

Write often and oblige your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

P. S. Tell Father I received the two dollars sent in his last letter. — E. P.

¹ After Christmas, 1862, “Lee ordered Stuart to conduct a raid north of the Rappahannock River to “penetrate the enemy’s rear, ascertain if possible his position & movements, & inflict upon him such damage as circumstances will permit.” Assigning 1,800 troopers and a horse artillery battery to the operation, Stuart’s raid reached as far north as 4 miles south of Fairfax Court House, seizing 250 prisoners, horses, mules, and supplies.” [Source: Wikipedia]

² From Perry’s account, we can surmise that Brig, Gen. Robert Cowdin (1805-1874) was a blowhard. In the battle at Blackburn’s Ford in which he served as Colonel of the First Massachusetts Infantry, he is quoted as saying, “The bullet is not cast that will kill me today.” On-line biographies of Cowdin’s service make no mention of his ever having been wounded in battle during the Civil War. However, the Boston Traveler reported that Cowdin was “slightly wounded” at Second Bull Run. When he failed to gain a promotion in 1863, Cowdin published (in 1864) a brief pamphlet suggesting that he had been forced out of the service by Massachusetts politicians because he did not share the same abolitionist views.

³ A regimental history of the 11th Rhode Island states that “for nearly three months the [regiment] did constant picket duty on the front which lay between Lewinsburg and Falls Church.” [History of the Eleventh Rhode Island, page 51]

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Page 5

Page 6

Hospital near Camp Metcalf

February 6, 1863

Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 31st inst. is received — also two papers of a later date for you receive my thanks. The last few days have been the most winterish of the whole season — some very cold weather accompanied with snow and rain. This afternoon it cleared off with a prospect of good weather tomorrow.

Col. Horatio Rogers, Jr.

By news received from Co’s C and K today. I learn that they are not doing duty yet but are taking things easy in Alexandria. Some say they are to garrison Fort Ellsworth near there. ¹ Colonel Horatio Rogers leaves here the first of next week to take command of the Second Rhode Island Regiment near Falmouth. The new band of this regiment commenced to practice yesterday. The boys subscribed eight hundred dollars for the instruments.

We have now nothing but iron bedsteads and cotton mattresses to sleep on. These bedsteads are made something like folding ladders as they can be shut up in a very short time so as to occupy but a little space.

There was a considerable of a fire last night at Fort Scott [near Arlington] burning down a negro’s shanty with its contents.

I am getting tired of doing nothing. Here I sit day after day in a room about the size of mine at home where only seven of us sleep, eat, and stay.

Evening. 7 o’clock. Your favor of the 2nd ultimo arrived this evening as also a letter from father of a later date. You say that I have not written about my health for some time. I don’t perceive much change for the last two or three weeks. I can’t gain much strength as long as this weather and mud continues as there is no chance to exercise. There is something inside not quite right yet but I am in hopes it will wear off in time. The doctor pays no attention to it so I suppose it is all right.

I received the five dollar bill for which receive my thanks but as I have been unexpectedly paid off and have already fifteen dollars of that left, I think best to return it as I shall not need it for a long time — and another thing, where a person has such associates as I am obliged to have, money is not very safe. Since I have been in the in the hospital, I have lost two knives worth $1.50, my gold pen, tin cup, tin pan. These must have been stole as I could not have lost them at the time. You must not take offense at the return of the money as I should have accepted it under other circumstances.

The picture I will send you as soon as [I] can get where they take them. Please write me if you would like a full length portrait with my equipment on and without any whiskers. It is getting late so I must stop.

From your affectionate brother, — Edwin

¹ Companies C & K did not garrison Fort Ellsworth as rumored. Rather they were ordered to the Camp of Distribution on the 3rd of February. This camp, located about two miles from Alexandria, was utilized for the distribution of the men discharged from hospitals, and the numerous stragglers gathered from all parts of the country. Companies C & K returned from detailed duty on 18 March 1863.

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

[Camp of Distribution near Alexandria, Va.]

Encampment of Guards

February 8, 1863

My Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 26th and 28th is received — also a letter from father of the 27th ultimo. All three arrived the same evening. I am ailing somewhat today so that the doctor excused me from duty today. Night before last I did not get any sleep and was out four hours in a snow storm. I suppose I overdone but as shall not be on duty until Friday again, I shall try to be all right then.

The weather here for the last few days has neither been one thing or another. It rains, snows, hails, and fair weather — all in five minutes. Day before yesterday there was a fair sized battle fought in the vicinity of Clouds Mills about three miles from here. Some of the New York regiments which were situated on Upton’s Hill when father was here had an inkling in the matter.

You wished to know if my hair continues to fall off. It does! I expect it will all come off.

Co. K is a city company — the Second Christian Association. I like this detached service better than being with my regiment because here there are no dress parades, no knapsack inspections, and no guard around the camp to keep us in, besides numerous little things which we are not obliged to do here.

Since the regiment was paid off in February, the restrictions on the camp have been [made] rigid. No one can pass off or on without a pass. Bayonets will not stop the men as they would in Dexter training grounds but bullets will.

Inclosed I send you the soldier’s prayer. I don’t mean the one he says when he has to turn out in the middle of a stormy night to do four hours guard duty, but the one that is used on common occasions.

How does the new conscriptions law go down with the Northern inhabitants? Have you seen this conundrum? “Why is the government currency like the ancient Israelites?” — “Because they are the issue of Abraham’s and know not their redeemer.”

I should have sent you my picture some time ago if it had not been for some humor sores on my face. As soon as they get well, I will get one taken.

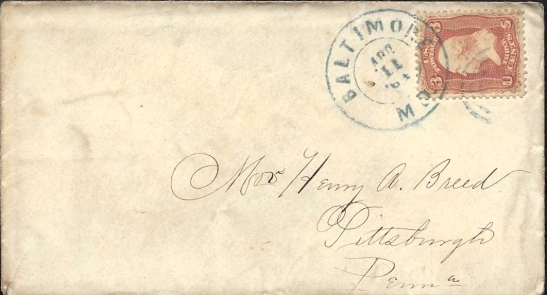

Thirty more skedadles [in this case, Union deserters] arrived yesterday from Fort McHenry, Baltimore. Some had no change of clothing or blankets and but two had overcoats. Some were dressed in citizen’s clothing.

Your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Camp of Guards at Camp Distribution

February 10, 1863

My Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 5th and 7th ultimo is received. Also two papers and a novelette.

I have again tried the vicissitudes of camp life and I hope that I shall have no ill health for it is no fun to be sick out here.

The new camping ground is situated in a much pretty location than ever before, being located on a high table land overlooking the Potomac. Camp Distribution is situated on the north side of the road leading from Alexandria to Camp Convalescent. In a former letter, I wrote you that men sent to Camp Convalescent who are able to [perform] duty are sent from there to their regiments. This is not so, for they are first sent here and then under guard outside of the picket line to their regiments at the front. This camp we are now engaged in guarding — it is rather hard looking. It consists of common A tents, pitched on the ground with nothing but Virginia mud for the men to sleep on.

“Some of them are sitting around the fire shivering with their blankets on.” — Edwin Perry

The remaining brigades of General McCall’s division arrived here yesterday morning but have not yet formed an encampment as they expect to move further. These men look rather the worse for wear. Some of them are sitting around the fire shivering with their blankets on. This morning the second and third relief were sent to take down some tents of long standing supposed to be unoccupied but inside they found a human being — if I may so call him — who was perfectly alive with many strangers. ¹ His feet were frozen and when found, he could not stand alone. I presume he had looked for a place to sleep and had crawled in here where he was attacked by these strangers who perfectly unmanned him.

It appears by your letter of the 5th that your patriotism has not declined in least. Before — and more since — I received that letter, I have been looking after the patriotic testimony of the volunteer soldiery, but best I can find is the common expression that, “they would see the government in hell before they would come again.” Of if they would print Green Backs until our time is out, they even would not hire them to stay longer.

You wished me to give you a history of a day in the hospital. This I can do in a few words. It is simply eat, drink, sleep & stay.

Tomorrow I expect to go to Alexandria if the weather is suitable and I can get a pass. Then I can write something new. I drawed some new clothing today — pants, shoes, and one shirt.

Today we received a very large mail, some of the letters being delayed two weeks. The weather is warm and pleasant and is fast drying up the mud, but I suppose the next thing will be rain. I received a letter from Hebronville today. I bought twenty pounds of hay yesterday and sewing two shelter tents together for a bed sack, I made a very comfortable bed to lay down in.

More soon. From your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

¹ Though I have not seen it used before in this context, I believe “strangers” must be a slang term for “lice.”

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Camp of Guards at Camp Distribution [near Alexandria, Va.]

February 15, 1863

My Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 9th ultimo is received. Glad to hear from you often.

Last night the second lieutenant who has command now, put me on guard between the hours of one and five for a difference in opinion which we had for a few days. I stood it very well although it deprived me of sleep nearly all the night. I did not receive the order until nine o’clock and I did not get to sleep until nearly eleven. I shall get an excuse from the doctor today and then he can go his length. It commenced to rain last night about dark continuing until now. I understood that a new colonel is soon to take command of the regiment. Hope he may stay longer than the other.

There are many rumors afloat concerning our joining the southern expedition but I place but little reliance on them. We are now going down the hill of our time and them men are beginning to count the days when they reach home. They have all seen the elephant, the romance of war, and are now ready to go home. The sick call has been numerous this week — a great many being sick with a cold.

Our quarters are now in the best of condition — all the condemned tents being substituted for new ones. All those in the distribution camp have to sleep on the ground. This causes a great amount of sickness. The doctor who has charge of the camp does things up in a hurry. For instance, a morning at sick call perhaps a hundred men are drawn up in line waiting their turn. The guard lets in the first man.

Dr: What the matter with you?

Soldier: I have a severe pain in my side, Sir.

Dr: Give him some liniment. Next.

Dr: What’s the matter with you?

Soldier: I have rupture, Sir.

Dr: Who told you you had a rupture. There is nothing the matter with you. Like to go to the convalescent camp again suppose! Clear out! Don’t you let me catch you here again. If I do I will put you in the guard house.

This is the way he examines perhaps sixty men in an hour. In fact, he has now more mercy for a man than I would have for a beast.

My hair is fast falling off my head. Would you have it cut off and run the risk of catching cold or let it remain?

I see you have sent me a box of rations. I suppose it will reach me tomorrow. Such things are always acceptable.

Day after tomorrow we shall have one hours and a half drill every other day. This is rushing things some if not more. I don’t know but he will try to make me drill but I think I shall go to the guard house first. The participants in the fight of which I wrote recently have been sent to the slave pens in Alexandria for the rest of their time. These two companies have nothing but soft bread draw that which is baked every day. Fresh beef three times per week.

No more this time. From your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Camp of Guards at Camp of Distribution [near Alexandria, Va.]

February 18, 1863

My Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 14th ultimo is received — also a box from you, for which receive my thanks.

I think everything arrived safe although the box was broke open on the way and nothing remained of the address except Co. C, 11th Regiment. My name was found on something inside. I received a piece of cheese, a pail of butter, a nice cake, five pies, a lot of apples, a jug of vinegar, a box of mustard, a paper of pepper, a bar of soap, some pins, thread and yarn, a lot of wine crackers, and a chicken. I think this is all. This is a very serviceable box — butter, cheese, and spices are the things. Today there has two more boxes arrived in the mess and we are having a merry time of it.

My strength is gaining everyday so that I am now on duty. Day before yesterday I was on the third relief guarding prisoners. Today I am on the same relief a guard at headquarters. All I have to do is to stand at the door and stop men without shoulder straps from going inside.

Yesterday it snowed all day and today the rain is carrying it off. I stood four hours yesterday in a snowstorm. And now let me say a word in regard to the three reliefs. The first and second go on at nine in the morning and stay until five at night at which time the third relief go on and stay until nine o’clock and are not again called out until five o’clock this morning. This gives us the whole night to sleep.

We have an odd way of keeping prisoners here. ¹ Two posts are placed firmly in the ground to which a rope is stretched across. To this the men are handcuffed. This gives them the liberty of walking back and forth perhaps ten feet.

We cannot get passes to go to Alexandria now except on business. My nerves are getting stronger so that I can look and see teeth pulled and dug out without my heart’s jumping. Dr. [Moses S.] Eldredge of our mess is doing considerable business. Yesterday he dug out a tooth while the person was under the influence of ether.

I have not received a letter from home for two weeks. I am afraid the letters have been miscarried or delayed in some way. Rumors of the regiment’s moving continue but no one seems to know. If we move again, I shall throw away everything but my blanket and perhaps a spare shirt. Carrying a knapsack causes the heart disease which prevails to such an extent in the army.

I want you to send me two or three pens of Potter & Hammonds, or some fine quills; those that father sent are too coarse to write with.

The manufacture of bone rings occupies the time of the men a great deal. While writing, there are four of the boys in the tent so engaged.

There is but little news in our little camp and as [I] write often, you must not expect long letters. It’s going [to] be one of the nights for guard — plenty of rain and slosh. Write often to your affectionate brother, — Edwin

P. S. I forgot to name the paper and envelopes father and mother sent. — E.P.

¹ The prisoners Perry refers to detained at Camp Distribution were military prisoners who had committed various crimes from desertion and murder to sleeping on duty or drunk and disorderly. In other words, they were Union soldiers, not Confederate prisoners of war. While confined here, many of these men were put to work on the fortifications around Washington D.C. though they were generally not good laborers.

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Camp of Guards at Camp of Distribution [near Alexandria, Va.]

Feb 26, 1863.

Dear brother,

….I think you would like to know our little family. I propose to give a little history or rather biographies ofthe several individuals. In the first bunk we come to Corporal Eldridge, a dentist by trade and a man of considerable importance — at least so he thinks. He has a chair with a back in which after eating his meals he luxuriates in a cigar and the New York Herald. With him sleeps a man by the name of [Daniel C.] Snow — a jeweler by trade and I think once a professional gambler. He is always sick but never can get excused by the doctor. In the lower bunk Roger [L.] Lincoln and a man by the name of [Alanson] Alexander. The last named is a young man (and here let me say that there is but two in the mess over twenty three) and a butcher in the city of Providence — a first rate fellow and full of wit. In the upper bunk of the next tier is Orin [F.] Munroe and Edwin Perry. These characters I suppose you know. In the lower bunk sleeps two by names of James Buchanan and Charles [W.] Brown. The former is a jeweler and a good singer and withal a good mess mate. The latter is a gentleman by occupation, of much talent and a good education. Joseph [W.] Guild and a German by the name of [William] Thiel occupy the top bunk of the next tier. The first you know and the latter is by trade a tailor. He has served twelve years in the German service as a soldier. I like him much as a man. He has but little to say. The lower bunk is occupied by Corporal [Frank B.] Mott and his brother [Eugene]. These complete the seventh mess in Company C….

your affectionate brother, Edwin (Perry).

Camp of Guards [at Camp Distribution near Alexandria, Va.]

Sunday, March 8th 1863

Dear Brother,

Your favor of the 2nd and 4th instant is received. [I am] always glad to hear from you often. We have not had any good weather here for a long time. It rains, snows alternately making a sea of mud to tread through.

The Camp of Distribution is moving today. The First and Third Army Corps go today — that is, those armies who are absent from their respective regiments. A detachment of Co. H, First Rhode Island Artillery was here today looking after deserters. This is the artillery which were encamped a short distance from Dexter’s Training Ground at the time the 12th [Rhode Island] Regiment had their trouble. This squad said that all of half of their company had skedaddled to quarters unknown. So much for the patriotic volunteers of Rhode Island.

One of our prisoners took french leave of absence while Co. K was guarding them last night. A member of this company has been tried by court martial and sentenced to two years hard labor on the Rip Raps without pay. I believe the charge was striking a superior officer.

I expect to draw some more clothing in a few days — say three pair socks, one pair of drawers and one pair of shoes. Our Second Lieutenant [Seth W. Cowing] left us today. He takes a position in the Navy. He could not go too soon so my best wishes are for his poor success. Lieut. [William A.] James has command here now.

You inquire about Wilbur Slocum. I have not seen him for some time. Since I saw him, he has been reduced to the ranks — what we call broke off his sergeant’s warrant. I am very sorry for him for he has done me many favors.

We are all eagerly looking forward to the time that the draft will be put into execution. Perhaps they will draft me if I ever land in Little Rhode. And then again perhaps they won’t. I will give two cents a head for all nine-months men they draft in government shinplasters.

New has “played out.” There is nothing new about this guard duty. It is the same thing over everyday. Write as often as usual to your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

Page 1

Pages 2 & 3

Camp of Guards [at Camp Distribution near Alexandria, Va.]

March 11, 1863

Dear brother,

Your favor of the 7th instant I received last night and now hasten to reply. For the last two days I have not found time to write a letter on account of want of time. I was sorry to hear of your ill health. Have you ever tried a medicine for your wakefulness of which you speak? A whiskey punch or Dover’s Powder I should think might be good.

Yesterday I paid a visit to Fort Worth ¹ beyond Fairfax Seminary. It is situated on the brow of a high hill overlooking a large valley. The fort mounts about thirty guns of which the largest throws a one hundred pound shot. The bed and carriage is constructed of solid iron. There are a number of large Parrott guns of beautiful workmanship. Besides these and some common sixty-fours, there are some eight mortars placed on massive beds of iron. There are also two pieces of light artillery bearing the inscription “Whitworth Guns Presented by the Loyal Americans in Europe to the Government of the U.S.” You will remember of reading about this about a year ago. These are made of steel and are bronzed like a musket about ten feet in length and breech loading.

I also paid a visit to the grounds of Fairfax Seminary, This place I suppose father can describe as well as I.

Fairfax Seminary

We — that is the mess — have formed a debating club to discuss the political questions of the day. This together with cards and checkers we make out to pass away our evenings when not on duty pleasantly. This evening we discuss the question, “Resolved. That the press is more powerful in influencing the minds of men than the tongue.” I will give you an account of the debate in the next.

Tomorrow I shall send a record of this company to you and also one to father, not that I feel particularly proud of having my name placed on this record of the 11th Regiment but because I thought I would make you a small present and this might be acceptable. Be careful in opening it. Tell father to enclose me a dollar in my next letter as my funds have all been used with the exception of two dollars which I have lent in the mess. I cannot get it until we are paid off.

No more this time. I will try to write more in my next.

From your affectionate brother, — Edwin Perry

¹ Fort Worth was located on Seminary Heights about one and one-half miles west of Fort Ellsworth, and one and one-half miles south of Fort Reynolds.

Pages 1 & 4

Pages 2 & 3

Camp Metcalf, Virginia

March 20, 1863

Dear brother,

….The mud is so deep here that it is difficult to tell whether you are traveling by land or water. In some places the mud is a foot deep. I received the two dollars from you for which receive my thanks.

First page of Letter

I saw Wilbur Slocum yesterday. He told me about his misfortune and asked me to write to you the particulars. On Miner’s Hill he was sergeant of the guard one day. His relief came off at twelve o’clock at night and was to turn out at two ready to go on again at four. He asked the sergeant of the second relief to wake him up before two o’clock. Ten minutes before two, he waked up and hurried to wake up his men. While doing this he received a message from the officer of the guard that if he was not on the ground in three minutes, he would report him to the Col. He made out to get his men there a minute or two after time. Then they had to stand hours understand before they went on guard. This is the reason why he was reduced and this is the red tape of the matter. Since then Gov. Sprague offered him a commission in the 12th Regiment. But his folks would not permit him to take that chance. He expects to have his old position as soon as our new Col. arrives. Please keep this a secret.

Yours in haste, Edwin